My book comes out in a few months, and I am terrified. I am scared that no one will read it. I am afraid that it is not good, but at the same time, I am afraid of what it might mean if it is. I worry people will not want to engage with it because it is poetry, and poetry so often carries the connotation of being confusing, structurally strange, or too intellectual for casual reading.

And I hate that.

I am drawn to writing that is emotionally deep but simple enough to understand. Work that is not buried under fancy language just to appear complex or sophisticated. I have always said poetry is the only way I know how to take complicated emotions and turn them into something digestible. I do not believe poetry should push people out. It should invite them in and ask them to sit with it. Poetry, to me, should be a bridge between the heart and the reader, not a locked door.

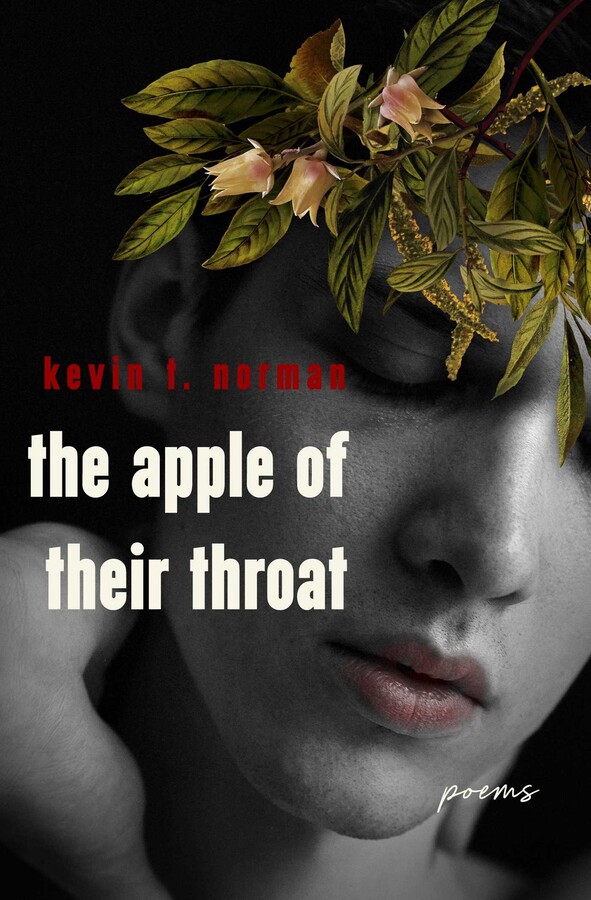

My book, The Apple of Their Throat, is my third collection but my first traditionally published one. My first book, Shelter, was self published in 2018, and looking back, it makes me smile and cringe. It was written in the middle of a breakup and reads like an unfiltered emotional diary. At the time, I was trying to emulate what I would call Instagram poets. I did not understand structure or line breaks, but I knew what I felt and I tried to translate that as honestly as I could.

Then, in 2024, I self published another collection as a small passion project called The Transformation of Fruit. That book was more mature and more intentional, but still messy and still raw.

Over the last six years, I submitted my work for publication and was rejected again and again. I revised, restructured, rewrote, and wrote entirely new poems, all of which eventually led to The Apple of Their Throat. Looking back, I was not ready to be published. I do not think my writing was bad. It was just unstructured, raw, and a bit directionless. With The Apple of Their Throat, I found what I wanted to say, how to say it, and how to do so in a way that respected my ethos of what poetry can be.

The Apple of Their Throat is a love story. To the self. To old religions. To love itself and to heartbreak. I call it a memoir in verse because, in many ways, it is. It is my life and my story, but once it is on the page, it no longer belongs to me. I would not even say it is ours. These words belong to you now.

The poems may be specific to my experience, but the emotion beneath them is universal. That is my hope, that you feel that universality when you read them. My partner, who is not religious, once told me that the poems he connected with most were the religious ones. That surprised me, but it also confirmed what I have always believed. When the emotion is true, the subject does not matter.

This book is about love, heartbreak, family, queerness, selfhood, and the beliefs we internalize to find our place in the world. I fell in love with the symbolism of fruit, how it is considered the birth of sin and how queer people have been called “fruit.” And while these poems can be read in any order, they do tell a story with a full arc from the first page to the last.

I want to explain everything about this book to you, but I think now I have to let it speak for itself.